What's the value of a fox-kit moon?

My sense of wonder is a salve for the sacrifices’ sting—and I would trade even more for moments like this.

Drafted in Long Pine Key at Everglades National Park on February 12th, as a male and female cardinal danced outside the van’s open doors.

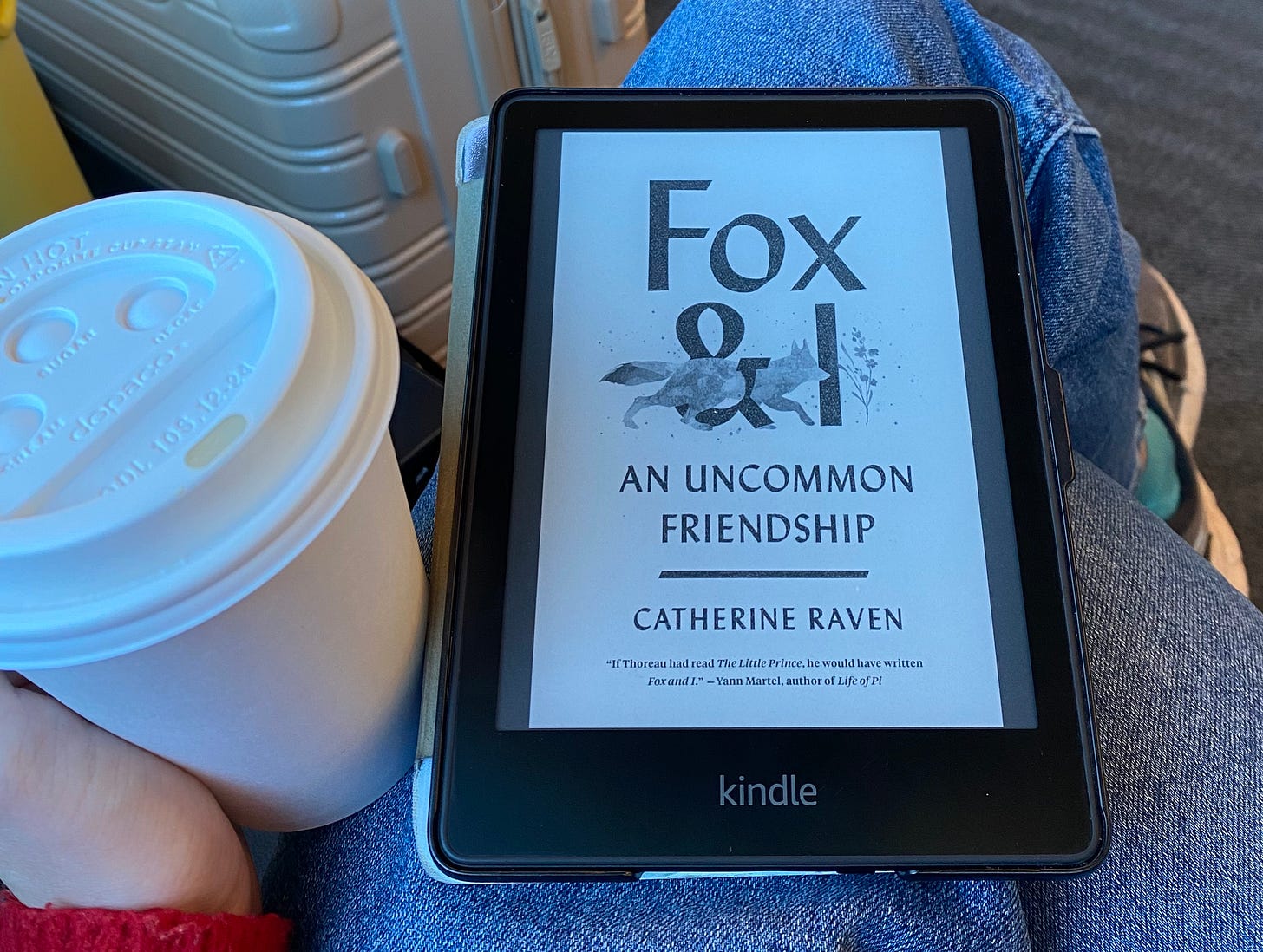

Catherine Raven, a solitary biologist in the mountains of Montana, wrote about befriending a wild red canid in her memoir aptly titled Fox and I.1

The most magical moment in the book occurs one night when Fox brings his kits—baby foxes! I nearly squeal with delight imagining a rough version of the scene—to Raven’s cabin. While he settles for a nap, she watches his progeny tumble around and atop each other, close enough to touch. They are illuminated by the moon and awash in fresh air.

Afterward she talks about assigning value to these events. Raven gives up so much—close human connection, quick access to resources, career opportunities—to live the way she does. Are the sacrifices worth it? What would she trade for another night of fox kits?

Nearly everything, she answers.

Me too, I think. Of course it’s presumptuous to compare my life directly to Catherine Raven’s—she is infinitely more badass than I am—but the last two years primed me to understand her calculus. We’ve given up dozens of previous staples to travel full time in a converted van. On occasion it is exhausting. But when you ask if the sacrifices are worthwhile? I do not hesitate: Yes, yes, a thousand times yes.

I have never witnessed a fox-kit moon, but I have fallen asleep to wolf howls outside Yellowstone National Park. I have heard bats echolocating—rare, these clicks audible to human ears—just above my head in Utah’s desert. I have gasped at Florida tree snails, Liguus fasciatus, shining in their narrow Everglades range.

I see the Milky Way so often I almost forget how precious the sight has become in our artificially lit human world. Lately I take pride in knowing, without having to think, the current phase of the moon simply because I’ve spent so many recent nights outside. This morning I stayed in bed for half an hour counting bird songs through our open back doors. Yesterday Sean and I ambled a boardwalk trail more slowly than my past self could have imagined, gasping at the smallest air plants you’ve ever seen and strangler figs’ wild acrobatics and white lichen decorating tree trunks in a pattern reminiscent of my hometown’s dairy cows.

I do not always know where I am going to sleep, if we can park without disturbance, when I will next find a fully stocked grocery store. It is scary to get sick on an island in another country thousands of miles from the place you once called home and only hope the local pharmacy can help. We constantly befriend the world around us—try to, anyway, balancing our own curiosity with the removed reverence fellow creatures deserve—but always through the ache of missing our human friends, longing for the ability to call them up last minute and ask if they want to meet for a beer.

I hurt, sometimes: physically, emotionally, deep in my chest.

But my sense of wonder grows. Lights up with the fireflies, sprints with the deer, dives on the ospreys’ outstretched wings. It is a salve for the sacrifices’ sting—and I would trade even more for moments like this.

Passages I highlighted in Fox and I

Page 22: You don’t need much imagination to see that society has bulldozed a gorge between humans and wild, unboxed animals, and it’s far too wide and deep for anyone who isn’t foolhardy to risk the crossing. As for making yourself unpopular, you might as well show up to a university lecture wearing Christopher Robin shorts and white bobby socks as be accused of anthropomorphism. Only Winne-the-Pooh would associate with you.

Page 34: I wasn’t trying to emulate normal people, but I did like knowing what they were up to.

Page 233: In the twenty-first century, everyone wants everything to be natural—with a few exceptions: medicine, transportation, energy, communication, televisions, wrinkles, cell phones, bad eyes, weak hearts, worn knees, small boobs, old hips, indoor temperature. The more we humans pamper ourselves with manmade toys and tools, dressing in polypropylene, Gore-Tex, and nylon fleece and availing ourselves of dentures, braces, statins, vaccines, diet pills, hearing aids, and pacemakers for everyone over the age of seventy-five, the more we demand that unboxed animals stay natural. Like a seesaw with humans on one side of the fulcrum and wildlife on the other, we sink further from a natural life and force wildlife closer to it. Our pursuit of the natural life is as vigorous as it is vicarious.

Page 245: Those of us who have barnacled ourselves to inhospitable places may be trying to avoid people not because we do not like people, but because we love the things that people destroyed. Wild things. Horizons. Trolls.

Page 265: Looking back, I would say that when a person thinks they are wrong for doing something that feels right, well, then, the definition of wrong needs to shift.

Page 293: lack of imagination is not a career choice, it’s a personality crisis.

The linguistics nerd in me especially loves the formality of this title. Raven and Fox are officially in subject form—I rather than me—but the “and I” construction is also growing common as a “more polite” way to refer to ourselves as a duo with someone else. It’s subtle but fitting for the way she describes her relationship with this wild fox—the way she emphasizes their mutual respect.

With photography, I sometimes find that beautiful and interesting sights are diminished slightly by either the act of setting up and taking a photo or the FOMO (for lack of a better term) of not taking one. Maybe writing better allows us to capture special moments after the fact, but do you ever find yourself distracted, thinking, "How am I going to describe this?" Just curious. I really enjoyed some of your descriptions in this piece.